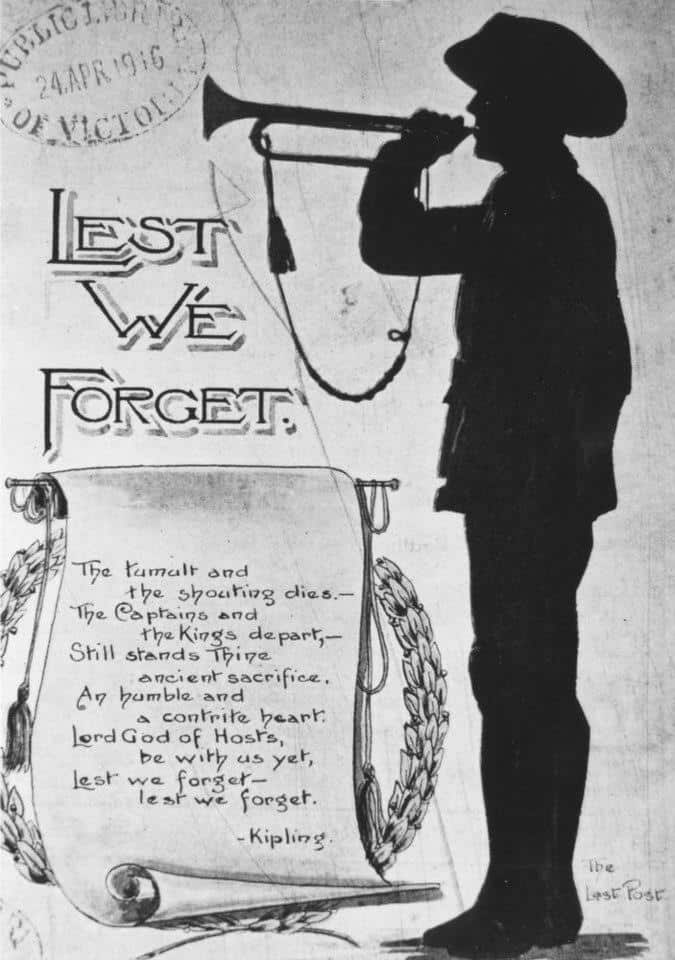

On May 25, 2020, the United States celebrates Memorial Day, a federal holiday dedicated to honoring and mourning military personnel who had died while serving in the United States Armed Forces.

Previously observed on May 30, it has been officially moved to the last Monday of May since 1971, purportedly to allow people to enjoy a long weekend (sounds familiar?).

However, veterans groups have decried the change saying people engage in vacations in revelry instead of visiting cemeteries and memorials to honor and mourn those who died while serving in the U.S. Military. The US flag is frequently seen on graves of military personnel in national cemeteries.

While there is currently no Philippine equivalent to Memorial Day, the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office and Armed Forces are pushing to have September 2nd officially recognized as Victory Week to honor and mourn military personnel who died while serving the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

“We have started informally building the surrender of Gen. Yamashita as Victory Week since last year, which we treat as the equivalent of the US Memorial Day. It takes a legislative action to establish it so we made it initially as a tradition until we could elicit acceptance,” said Brig. Gen. Restituto L. Aguilar (ret.), chief of the PVAO’s Veterans Memorial and Historical Division.

Even before that is officially recognized by the Philippine government, allow us the privilege of honoring and mourning some of our local heroes who perished during the Second World War in service of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) and the guerrillas of the United States Forces in the Philippines (USFIP), when the Philippines was still a colony of the US.

Although bitter adversaries during the Philippine-American War of 1899-1902 (still carried in American history books as the ‘Philippine Insurrection’), and the first and only colony of the US in Asia since that time, Filipinos never bought into Imperial Japan’s line they were here to free us from the American yoke as partners in the ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”.

The formal surrender of Japanese Forces in the Philippines held at Camp John Hay, Baguio – September 2, 1945

When the Pacific War broke out on December 8, 1941, with Japanese planes bombing Clark Field and other US installations in the Philippines, the greater part of the Filipinos sided with the US and when the USAFFE forces under Maj. Gen. William F. Sharp, Jr. surrendered to the invaders on 10 May 1942 in Malaybalay, Bukidnon, most of the American and Filipinos melted away in the hills of Mindanao to start what eventually became the biggest and most organized group of guerrillas in the 10th Military District, USFIP under Col. Wendell W. Fertig.

For this year’s Memorial Day, we honor and mourn some of our Filipino martyrs who fought and died in the service of their beloved Philippines and their adopted country the United States of America.

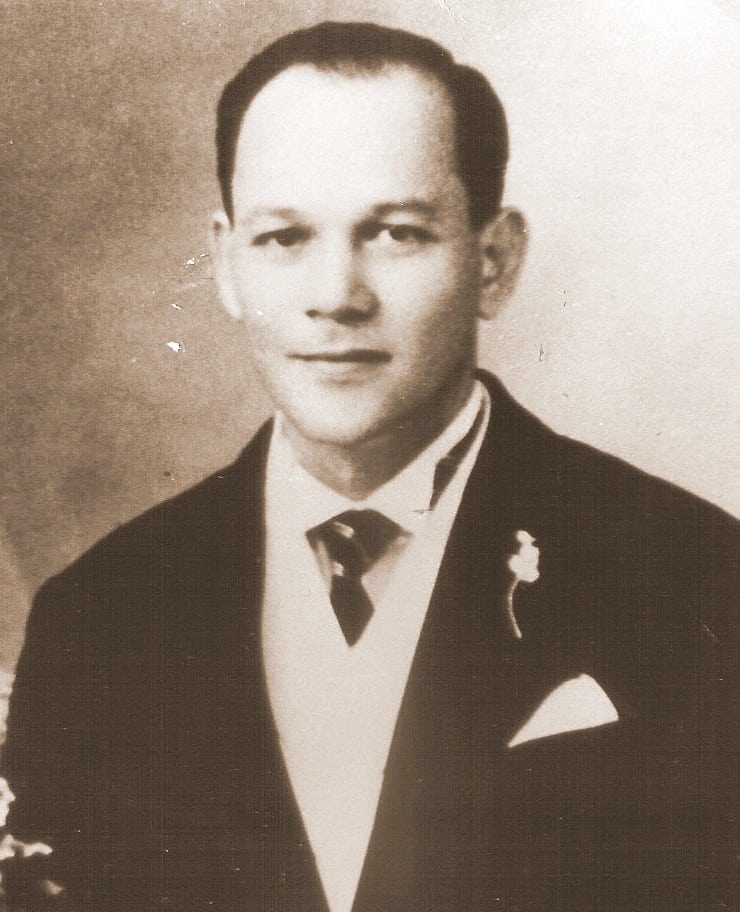

Capt. Antonio Julian C. Montalvan (Feb. 8, 1906 – Aug. 30, 1944) was a member of an espionage team as G-2, MC Liaison, and Intelligence Officer, of the 10th Military District under Fertig in Mindanao, who reported directly to Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Captain Antonio Julian Montalván G 2 10th Military District USFIP

As a medical doctor, he was able to get information by moving through various hospitals in Manila about Japanese troops in Mindanao, which he passed on to Fertig and which eventually reached MacArthur in Australia. As a member of a spy network, he helped establish coastal radio relay stations in Mindanao, the Visayas and Southern Luzon.

After three successful intelligence gathering trips by Banca to Manila from Mindanao, he was arrested by the Japanese Kempeitai (Military Police) in Tayabas, and was later detained and tortured in Fort Santiago and the Old Bilibid Prisons in Manila.

On August 30, 1944 he was executed by decapitation with the group of Senator José Ozámiz, and the Elizalde Group of Manila which included the writer Rafael Roces and Blanche Walker Jurika, the mother-in-law of guerilla leader Charles “Chick” Parsons. The execution took place at the Manila Chinese Cemetery.

1st Lt. Fidel Saa, Sr. of Cagayan, Misamis, was the 109th Regiment’s dental surgeon. He married Enriquita Mercado of Gingoog City with whom he had three sons: Le Grande, Fidel Jr., and Ruel. On 03 January 1944, he and four other guerrillas and one civilian were captured, tortured, and bayoneted to death when the Japanese ambushed their headquarters in El Salvador around 04 January 1945.

The other victims were 2nd Lt. Eufronio Jabulin, Sgt. Gregorio Macapayag, Cpl. Gerardo Saguing, Pvt. E. Eling and Chong Ing, a Chinese trader. The Japanese also captured Maj. Fidencio Laplap’s father Melanio and brought him to Cagayan where he was tortured and killed.

The Japanese had no reservations about the age of the suspected spied and guerrillas they killed. Sometime in 1942, Cox Banquerigo, an intelligence asset of the guerrillas was betrayed by a “friend” and neighbor at the Parke (now Gaston Park) who was an enlisted man with the Japanese-sponsored Bureau of Constabulary (BC). Only 16 at the time, Cox was brought to the Ateneo de Cagayan where he was interrogated, tortured, and beheaded. The guerrillas eventually caught up with the traitor and killed him at Barangay, Agusan.

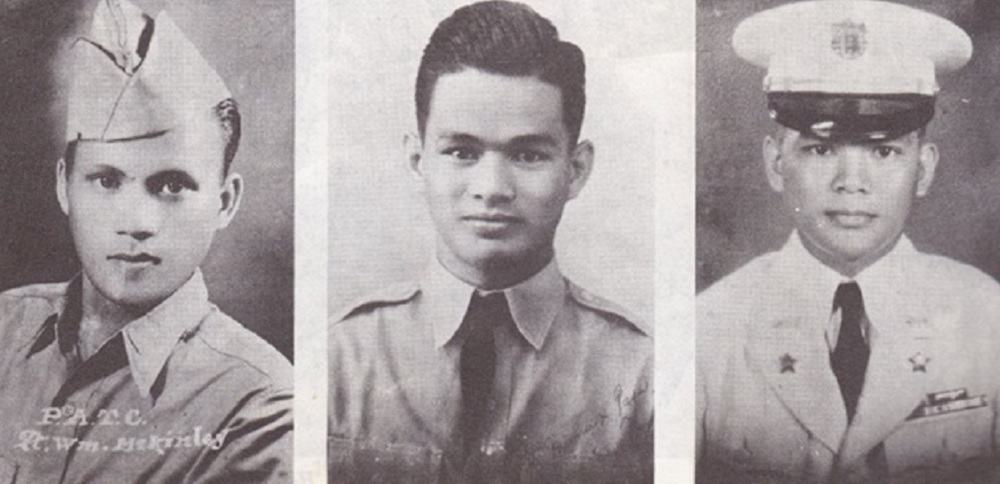

Perhaps the most remarkable Kagay-anon patriots were the Tiano siblings, for whom the Tiano Brothers street in Cagayan de Oro is named after, another story apparently is forgotten by the present generation. No less than six of the siblings, five males and one female, were involved in fighting the Japanese in World War II, making them our counterpart to the famous Sullivan Brothers of the US Navy.

The Tiano Brothers (from Left to Right) Sgt. Nestor Tiano, 1Lt. Ronaldo Tiano, and 2Lt. Apollo Tiano – MOGCHS 1980

While only the second eldest sibling Nestor was killed in action vs. the Japanese at the young age of 24, while repelling a Japanese attack at Aglaloma Point, Bataan on Jan. 23, 1942, this does not by any measure diminish the sacrifice of his five other siblings in the struggle against the Japanese Occupation during the war.

The eldest Ronaldo, a 1st Lt. in the nascent Philippine Army Air Force (PAAC), survived the Bataan Death March, but was released by the Japanese from the concentration camp in Capas, Tarlac and instructed to report to the Japanese headquarters in Cagayan. He came home wearing his full PAAC uniform. Instead, he joined the 120th Infantry Regiment under Maj. Angeles Limena as one of his staff. After the war he joined the newly organized Philippine Air Force (PAF) but left after 18 months to join Philippine Airlines (PAL). He died in a plane crash on Jan. 24, 1950.

Apollo became a 2nd Lt. and platoon leader of “C” Company, 1st Battalion, 120th Regiment, 108th Division based in Initao, Misamis Oriental. He died fighting with the 19th Battalion Combat Team (BCT) of the Philippine Expeditionary Force to Korea (PEFTOK) defending Hill 191 (also called Arsenal Hill) and Hill Eerie, comprising Combat Outpost No. 8 at the Chorwon-Siboni corridor in the west-central sector of Korea on June 20, 1952, while repelling a superior force of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army. The Philippine Navy’s BRP Apollo Tiano is named in his honor.

Uriel became a sergeant of “A” Company, 1st Battalion, 120th Regiment, 108th Division based at Pangayawan, Alubijid, Misamis Oriental, and ended the war in the Signal Corps.

The youngest brother Jaime was a private first class at only 15 years of age and served as a medical aide of the 120th Regimental Hospital together with his sister 1st Lt. Fe B. Tiano (RN), who was the unit’s sole regimental nurse at the regimental hospital at Talacogon, Lugait, Misamis Oriental.

As Cpl. Jesus B. Ilogon relates in his unpublished manuscript, Memoirs of a Guerrilla: The Barefoot Army,” Lt. Fe Tiano and PFC Jaime Tiano were engrossed in their hospital work, tending to the sick of the regimental hospital. They were so busy that they forgot to apply for their vacation, and when they did, it would be disapproved.” Truly a dilemma that our front lines in our hospitals and health care facilities could relate with!

“This is the story of the Tianos-brave and courageous, their battles are now part of history. While they went to war, their parents Emilia Bacarrisas and Leocadio Tiano and two sisters Ruth and Emily were left in Lapad (Alubijid, now part of Laguindingan), to stoke the home fires burning,” Ilogon noted.

Lt. Fe B. Tiano and her brother PFC Jaime during the Liberation from the Ilogon family archives

There are too many others, both known and unknown, who suffered the ultimate sacrifice in our fight for freedom, and it’s beyond our limited knowledge and capacity to mention all of them here.

But let this not diminish our recognition of their uncommon valor and faith in our ultimate victory that may serve to inspire us to withstand the trials of this unseen enemy which now confronts us the world over.

Thank you for your service to the Philippines and the United States of America! MABUHAY!

This article was written by Rene Michael Baños, a known journalist in Cagayan de Oro City and a History aficionado.

Recent Comments